On April 3rd 1884 a Captain Ada Smith was appointed as the new officer in charge of the Worthing Salvation Army. The first hall used by the army, known as the “barracks”, was down a narrow brick alley about eight yards long in an upper story of an old warehouse in Prospect Place. Half way up the alley was a side door of a liquor shop.

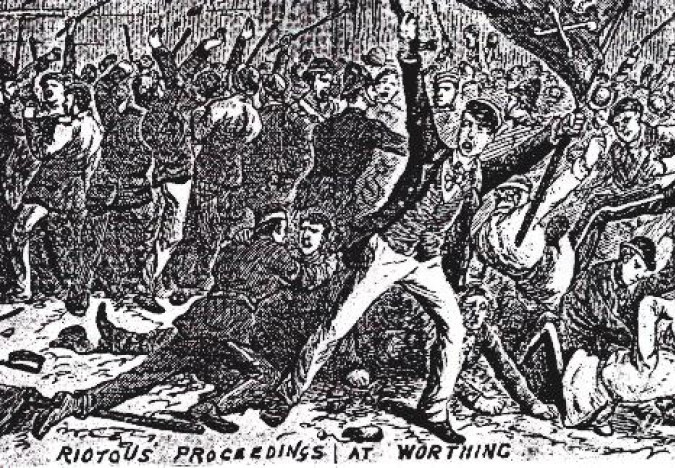

Until further notice Captain Ada Smith and her band were confined to barracks. General Booth wanted written assurance that the West Sussex County Constabulary would keep a fatherly eye on them. But the Chief Constable sat securely on the fence, he would treat both sides with impartiality. Booth was now beside himself and wrote a blistering memo to the Home Office saying that “Worthing magistrates simply refused to summon rif-raf molesting the Salvation Army.” the Home Secretary Sir Willam Harcourt stood by the letter of the law and had no power over local authorities.